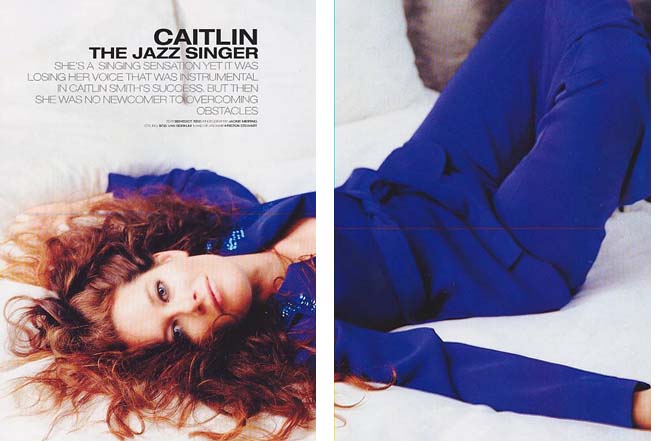

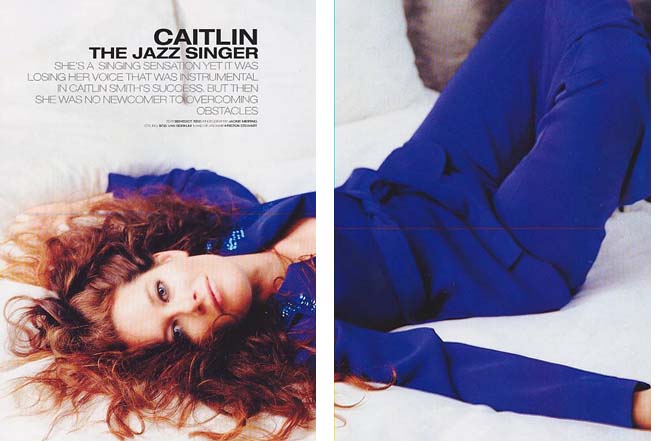

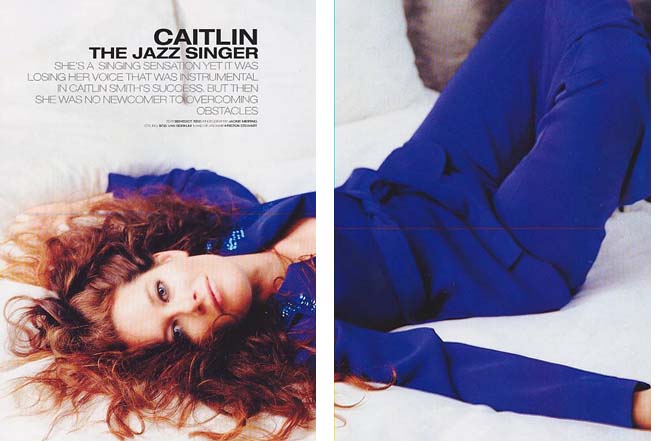

Lifestyle New Zealand Magazine

Winter 2002

“I’m lactose intolerant, go figure that one,” says Caitlin Smith of the jazz trio The Fondue Set while carefully searching her cafe lunch for any hidden pieces of mozzarella. This connection between her band’s name and her lactose intolerance is apt for someone who makes a habit of facing challenges head on.

It seems incredible that this icon of the New Zealand music industry, with a reputation as a talented jazz singer and also as a teacher for other professional singers, only got serious about singing in 1997. “When I was at uni¬versity I did sort of sing with a jazz trio, and later with a punk band, but I gave up the study of formal music. I was supposed to be doing a performance degree in music and I enrolled in it for two weeks but found it just so cripplingly narrowminded. I did a masters in politics instead. I still wanted to be aware of the world that I was liv¬ing in rather than just dissecting different cadenzas. So I did let singing slide for a while.”

Years later, after having worked for various environmental and human rights groups, Caitlin came face to face with a problem which has caused many other singers to retire. “I ended up developing nodules, which are like callouses on the vocal cords, plus I got tonsillitis and laryngitis. The doctors I went to see said, ‘Well, you’ve got to shut up then’.”

After enduring three weeks of “complete vocal silence”, Caitlin says she had to learn to sing again.

“That’s the reason why I teach now, because I had to go through the process of fully understanding the instru¬ment. You don’t really get to that process unless your instrument has failed you. There are lots of singers out there that are fantastic but they don’t know why. They may be the world’s most wonderful performers but for them it’s just an X-factor. Whereas for me to get a sound out I need to do a certain process, otherwise it actu¬ally doesn’t work. The whole thing about singing is you are your instrument, which is kind of weird. So I have to understand how my voice works and how I can make it work better. I’m fascinated by vocal pathology: why do you lose your voice? It is very, very psychologically bound. If I sing and I’m upset and tense and depressed, I lose my voice. It’s really interesting.”

Perhaps one reason why nodules didn’t slow Caitlin down is that it was not the first major challenge she had faced. “I’m legally blind. I can see 5 per cent from one eye and 10 per cent from the other. It’s sort of like an over¬exposed black and white movie. I don’t have rods, which make up the filter-system that allows you to perceive certain things. So I don’t actually get colour. And if it’s a sunny day out there it will be completely over-exposed; I’ll only see white.”

Caitlin won the Performing Arts Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind Achievers prize in 2000. “I think the more people with disabilities explain how they see things — explain their view of the world, their place in the world, the way they handle things — the more other people can accept what is different and learn from that experience as well. For example, the first thing you often do is panic when you see someone who’s doing things differently to you. You actually think, ‘How do I talk to them?’ and in fact the answer is just like you would talk to anyone else. You have to open your understanding as to how different minority groups exist.

“I’ve been able to have my musical career, which isn’t bad at the moment, it’s going incredibly well. My sight hasn’t been a hindrance or an obstacle for that, whereas previously it was. I was always involved with jobs and situations where I was being directly discriminated against because of my sight. It’s good there are lots of role models out there for blind musicians.”

She jokes “I think it’s been really helpful to me as a performer because not seeing audience reactions to things is probably sometimes a blessing. You’re ignored half the time as a jazz musician. I can easily say, ‘Hey, I can’t see people looking bored so I’ll just keep on going, no worries’.”

Caitlin has quickly established herself as a full-time musician, teaching during the day and performing an aver¬age of four three-hour gigs every week. However, performing live has resulted in some unexpected problems. “I’m having some issues I’m trying to wrestle with at the moment. One night alone, I had a guy who wrote some lewd poetry which he wanted me to somehow make into a lyric and sing. He would not let my hand go and invit¬ed me repeatedly to have dinner with him. There was also a stalker. They are just terrifying. When you’re blind you’re very easy to stalk as well.

“It’s been a troubling thing for me, but I think you do have to rise above it and say ‘Hey it’s just a passing phase’. I guess you’ve got to be positive rather than dragging yourself down with negative thoughts about it. There’s so many people who are really supportive of me.”

Caitlin admits that she has had difficulty asking the other band members (Steve Gerrish and Graeme Webb) for help when dealing with unwelcome attention. “That ties in with the disability thing. I don’t want to be a depen¬dent person, I’m fiercely independent. Accepting support from people and accepting assistance is actually a real¬ly hard thing to do. You do flip into this, ‘I have to do it myself mode which can be very destructive because people want to help.”

Last year she started the Professional Vocalist Collective, www.vocalist.org.nz, which she hopes to grow into a forum for singers to share ideas and experiences.

Earning a living as a singer means that Caitlin focuses on teaching as much as performing. “I have a real desire to teach. I really like teaching because I want to be able to help, essentially. And you know, I think I’ve found something that I can actually be useful in doing.

“The problem with classical singing is that it accepts only one style, as opposed to contemporary singing which says, ‘Hey that’s interesting, I can make my voice sound like a gorilla and that’s just as valid as any other vocal noise I’m going to make’. But with classical singing it tends to just say that there’s only one right way of singing. You use your voice this way and you strictly interpret songs as the composer intended them. It’s very formal and there’s such discipline involved. I still go for the discipline, but I’m really into the experimentation and finding out just what the voice is capable of.

“Most people have already taught themselves how to sing, because if you can speak, you can sing. You’ve got a set of vocal cords. A lot of people say ‘Oh, I can’t sing’. But that’s because their mother, their friends, their school told them they couldn’t sing. So teaching is about unblocking and unlocking the reasons why they haven’t worked on their singing. And the best analogy to use is skateboarders. They just have so much skill and discipline; they just get right back there on their skateboard when they fall off. You’ve got to say, ‘OK, so I make some horrible noises, that’s just part of the plan. I’m going to just keep practising and see what I’m capable of doing’.”

Possibly because of Caitlin’s open mind regarding what constitutes good singing, she has become a singing coach for a range of vocalists and bands, including Courtney Love, Tadpole, and Anika Moa. “The best way you can tell about musical performance is at source. You have to go and see them perform live and you have to see them in their environment. I then focus on how the singers can change their technique to prevent damage to their voice. However, I can only give so much advice, because it’s not always going to be taken. I was coaching one singer specifically for an album, but I realised no matter what I said it didn’t actually change the fact that the producer made her cry and still forced her to push her voice.”

As part of Caitlin’s ongoing investigation into singing technique, she travelled to New York last year to take lessons in American showtune singing, a style which Caitlin hadn’t previously explored. “It was interesting, [the teacher] suggested that I make my mouth like a rectangle, which was fun. And she said ‘Sing with your ears’. I literally tried to do that and it really helped.”

Despite the emphasis on technique in Caitlin’s pursuit of musical excellence, she is well aware that the core ingredient of any performance simply can’t be taught.

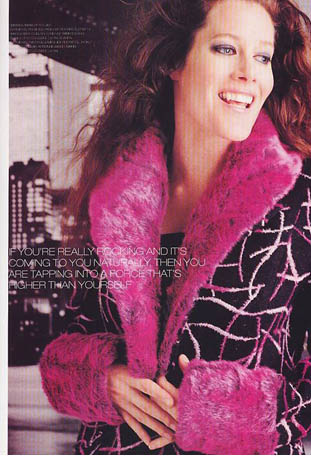

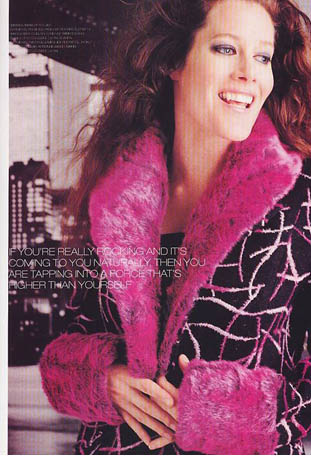

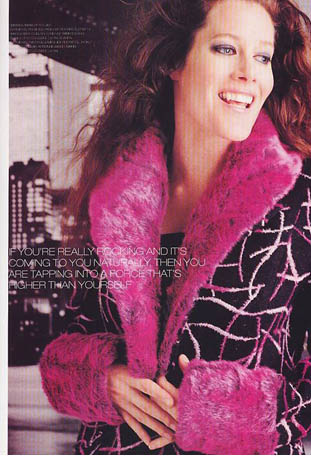

“When you are involved with any artistic sphere, you know that if you’re really rocking and it’s coming to you naturally, then you are tapping into a force that’s higher than yourself. Or it’s part of yourself but it also connects with everything else. So whether you perceive that as energy, force, chi, God, Allah, Buddha, however you say it, I do believe that there is a spiritual force.”

Perhaps it is simply the result of her dedicated research into all aspects of singing, but as an audience member at one of her live performances, I couldn’t help but feel that Caitlin Smith has soul.