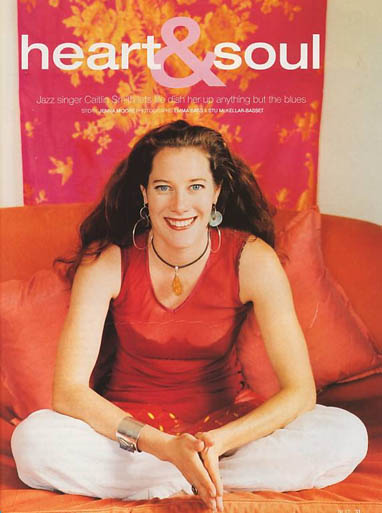

Next Magazine by Jenna Moore

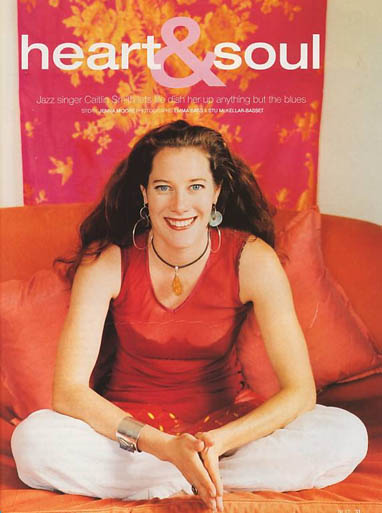

Jazz singer Caitlin Smith lets life dish up anything but the blues

April 2003

And I’d sell my soul for total control… over you.” Do you recognise the song, The Motels’ Total Control, from the Subaru television commercial? No? Okay, then what about the catchy tune on the Woman’s Day ad, Just Can’t Get Enough? Or Freedom, the soundtrack to the ad for breast cancer screening which sounds as if a choir’s behind it? These organisations haven’t had to shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars to secure the rights to the original recording. Those dulcet tones you’re hearing pour out of Caitlin Smith’s mouth. And the choir? That’s the same voice overlaying itself.

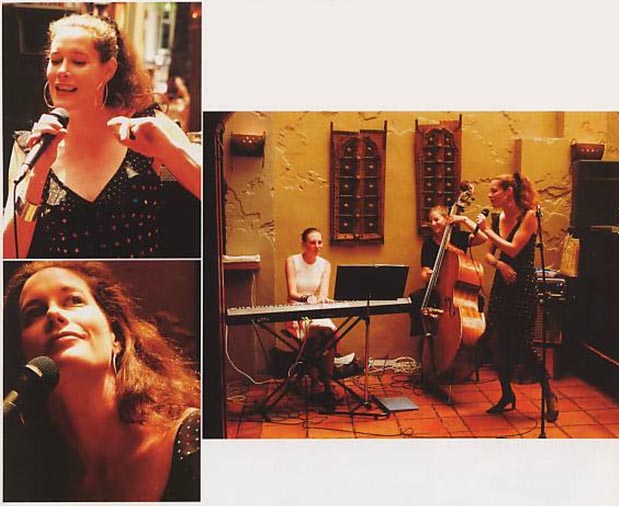

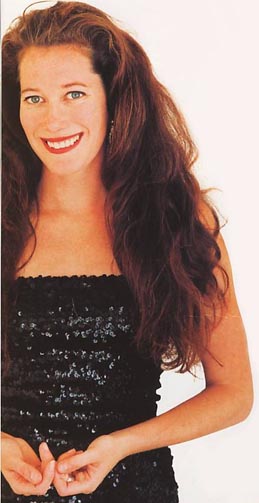

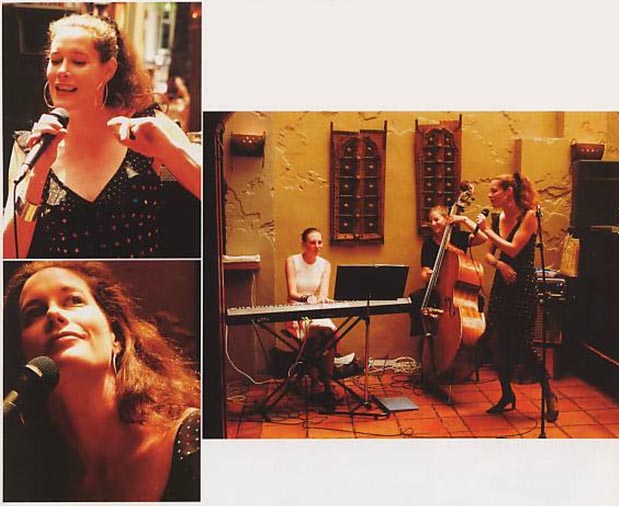

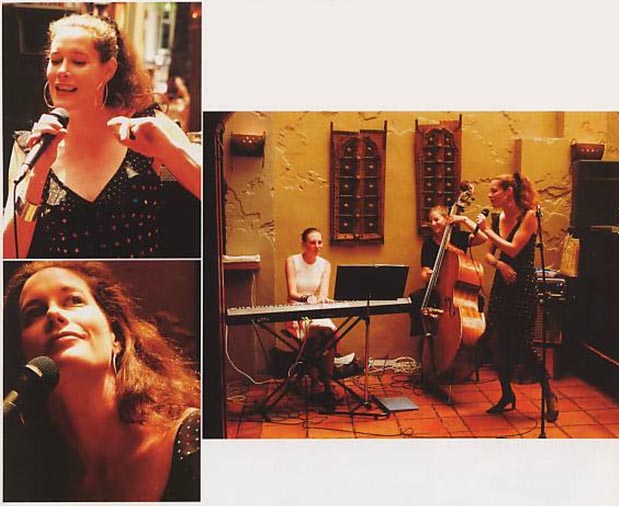

“I see myself as the underwire bra of the New Zealand music industry,” says Caitlin, 31. “I’m the one behind the scenes, singing jingles, helping with background vocals and voice coaching.” Caitlin is the lead singer in the jazz band The Fondue Set, with whom she’s released two CDs, Stick A fork In It and In A Blue Vein. She spends most of her time teaching her craft. She’s also -worked with many well-known names – The Datsuns, Anika Moa, D4 and Betty-Anne Monga from Ardijah; she helped Courtney Love warm up her voice for Big Day Out and undertook the on-screen coaching of made-for-TV girl band True Bliss.

“I’m a troubleshooter, really. Often a producer wants a certain sound and doesn’t know how to achieve it. I know what they want and how to get it,” says Caitlin. “The student does the work, I’m just the guide.”

Caitlin’s diminutive frame and mane of long auburn waves are offset by big blue eyes. Eyes through which she has only limited vision. “I’m legally blind but 90 per cent of blind people have some vision. It’s like the difference between stone deaf and profoundly deaf,” she says. “For instance, I’m wholly colour-blind but I’m light-sensitive which means I can see your outline and that you’re wearing a dark top and have dark hair.” She’s right – but can she see if I smile at her? “There are 7000 muscles in the face,” she says. “I can’t see actual facial expressions but I can hear them in the voice; I can tell if someone’s smiling.”

On initially meeting and speaking with Caitlin it’s hard to tell she’s visually impaired, unless she’s reading, in which case she must hold the page close to her face. In layperson’s terms she has five per cent vision in one eye and 10 per cent in the other (or technically, her visual acuity is 3:60 and 6:60 respectively). Simply put: what fully sighted people would see at 60 metres she can only see at three metres.

“I had mobility training at primary school. I should use a cane but I don’t because you become public property and I want to stay as fiercely independent as possible,” says Caitlin.

“We only need movement, memory and shape to get around; we don’t need finer detail. Fully sighted people are reliant on having more information, but most of it’s in the mind. Sometimes I talk to garbage bags and pat them thinking they’re a dog, and crossing the road can be a challenge.”

What most of us take for granted, Caitlin depends on. Next time you’re at a pedestrian crossing take a look at the box with the press button. “The boxes with the little button have a dent underneath where you put your finger and it gives a little prick when it’s time to walk. The ones with the larger buttons vibrate,” says Caitlin. “I think I rely on hearing, so that sense may have been strengthened. Sight is the preferred sense for most people – but think about touch, smell, taste and hearing. They’re all amazing.”

Caitlin, a member of The Blind Foundation, was a spokesperson for Blind Week and has also made a CD called Journeys with other blind musicians. “I’m lucky to have great role models,” she says. “Minnie Baragwanath rocks. She works for the [Auckland City] Council as a disability adviser and she’s a role model for me. She’s 32, partially sighted and she ran the New York marathon. I admire high-achieving women who haven’t sacrificed their souls and become bitches. Minnie’s successful but she’s also helping other disabled people.”

Because of her sight Caitlin can’t drive but apart from that inconvenience little seems to hold her back. She’s outspoken, obviously well-educated and passionate about what she does. However, she’s the first to admit she “kissed a few frogs to find her prince, in relation to getting the right job”.

Born in Toronto, Canada, Caitlin’s family came to New Zealand when she was a “wee nipper”. Her sister, Penelope, 33, lives in Amsterdam and her brother, Matthew, 34, is a detective sergeant in Auckland. Her father, Don, is a retired English professor and her mother, Jill, a retired schoolteacher. “There are five generations of teachers in our family,” says Caitlin. Perhaps unsurprisingly the family background is musical, too. Jill is a singer but she didn’t pursue it as a career.

Caitlin graduated with a masters degree in politics with first-class honours in 1994. Her specialty is conflict resolution wifh an environmental focus. She went on to work with ECPAT (a network of organisations campaigning against the commercial sexual exploitation of children), Greenpeace, die Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society and Trade Aid. But she’s come up against discrimination. For one union job she applied for as a researcher, she made it to a shortlist of two. It was decided that she might not be “capable of doing the close work as it’s defined. Hul-lo, how did they think I’d got through what I’d already done?” asks a frustrated Caitlin. These days she’s her own boss and in demand. “I love singing, funk and soul mostly, but I never thought it would be my career,” she says. “I looked at all my options and decided which was the one I really wanted. A lot of people don’t take it [singing] seriously. It has to be a primary focus.” She’s kept busy performing but it’s teaching that’s her mainstay.

“Teaching is energising and fun but I’m quite a disciplinarian,” she says. “It costs $50 per hour and for most people, if they’ve worked hard to earn their money, they don’t take the process lightly.” Caitlin also teaches at the School of Performing and Screen Arts at Unitec and at Auckland University’s School of Creative and performing Arts (SCAPA). And she writes songs.

“I’m a workaholic,” she smiles. “I’ve been doing this [teaching, performing and writing each week] for months. Sometimes I think I must be bonkers. But I love teaching. I learn so much from my students. It’s symbiotic; when I’m performing I take something back to my students and when I’m teaching I take something back to performing.”

Caitlin’s private students aren’t always high profile. They may be someone who’s always been passionate about singing but, for some reason, has never pursued it until now – and Caitlin’s right behind them. “A lot of people are scared in case they’re ridiculed – particularly in our culture – but you can make career shifts at any time. If you’re passionate about something, that’s the path you should be on,” says Caitlin.

“You’ll find your own voice. It’s a bit like therapy. There’s a book called The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron that I’m evangelical about. It’s about unblocking ourselves from excuses for not pursuing creative avenues.”

Even writing songs is something Caitlin is adamant it’s never too late to try. “You can start with lyrics or you can start with a melody; it might just come in the middle of the night,” she says. “Linn Lorkin is an incredible piano player; most people know her for her song Family at the Beach. She wrote her first song at 34.” But, by the same token, she was told not to give up her day job.

Caitlin has also been a singing student. “I’ve had several teachers and I’ve taken what I could from each one; it’s an ongoing process just like playing the piano or guitar,” she says. “I went to see Catherine McGreedy-Rosser, a classical teacher. You can get through life without tutoring but I had damaged nodules from my days in a punk band and I got to the point where I had to learn a lot of technique. Many teachers don’t want to take on damaged puppies but I was lucky.” Caitlin was in New York in 2001 where she had one lesson at the New School University two days before the towers came down. “I thought about making a go of it there. It didn’t seem impenetrable,” she says. “But my training’s been very ad hoc – lateral rather than lineal. I’m still learning. I’d love to go overseas and sit at the foot of some guru like [American jazz vocalist] Rachelle Ferrell.

“Candi Staton, Esther Phillips, Joni Mitchell… I like singers whose voices are intelligent. With a singer, the more authentic you are, the more your personality’s going to come through. For instance, she may not be technically perfect by definition but Nancy Wilson says more in three notes than most singers would in an entire album – it’s the meaning she puts into it.”

On the downside, Caitlin notes the recording industry is notoriously fickle. “The pop market works on idolatry. People love to worship and if we haven’t got a spiritual belief we’ll find something to worship,” she says. “Music is an art, it shouldn’t be a commodity.”

Her outspokenness has at times landed her in hot water. “I was fired from the Popstars show because I advised the girls to get legal guidance,” she says. “The producer thought I was overstepping my boundaries as a vocal coach. They’re all following their own paths now and doing well. Ultimately, success and longevity depends on how driven you are.”

Meanwhile Caitlin’s own schedule doesn’t look like it’s letting up any time soon. She’s gearing up for the Taranaki Festival this month, the Waiheke Jazz Festival at Easter and she plans to travel again during the European summer music festivals. She regularly performs at weddings over summer. “Weddings are great fun because they’re such a celebration,” she says. (For the record, to have Caitlin perform at a wedding costs from $900 for a trio.) “Performing is hard work,” she says. “I’ve given up having a social life due to tiredness. A lot of musos have a hectic schedule. You have to deliberately isolate yourself, which can feel very selfish.”

Her goal is to win respect from fellow musicians. “Fame and fortune aren’t on my list, I’d just like to know my instrument is respected,” she says. “I’m useless at self-promotion, I bumble along.” For now this bumbling includes a new CD in the making which incorporates her own material and collaborations with Jason Smith (no relation) of Platform Studios. E